History

Introduction

Portmarnock has been inhabited for many centuries – from the late Neolithic or Early Bronze ages, through Early Christian times and the coming of St. Marnock, through Medieval and Post Reformation times up to the present.

Saint Marnock’s Church

Saint Marnock’s Church

Plans by the local Church of Ireland community for a church in Portmarnock Parish were initiated in 1773. A site was obtained from the Earl of Milltown in a field known as the ‘Bean Park’. The Sexton’s House was built in 1785. In1788, the new St.Marnock’s church was completed and a Parish Clerk appointed. The church was consecrated in May, 1790, and, a year later, the glebe-house for the minister was built. This was on church land at Cloghran, the ‘Glebe of Portmarnock’, which, (while ‘detached’ from its main parish area), became one of the ten townlands of Portmarnock Civil Parish. Headstones in the churchyard commemorate members of the Alley, Blythe, Donald, Lawson, Lilburn, Richardson, Trumbull, Truscott, Von Der Nahmer, and Wall families. In 1873, Portmarnock parish was united with that of Malahide, but the church continued in use until 1960. The church is now in private ownership.

The Sexton’s House

Built in1785, the Sexton’s House later housed the first school in Portmarnock, the ‘Parish School’. A teacher there, John Neal, was appointed by the Archbishop in1807 ‘to officiate as English School Master of said parish’. The school was sustained by local subscription and a grant from the Lord Lieutenant’s School Fund. The school operated until the mid-19th Century, after which the building was used for various parish purposes. Like the church, it is now in private ownership.

The Blacksmith’s Forge

A blacksmith’s forge and residence was built here, beside the church, by John Donnelly in the early 1800s. Horses of nearby landowners and those of carters were shod at the busy forge. Items such as gates were made and farm implements repaired. In 1901 four blacksmiths, Francis Donnelly, aged 74, and his three sons, Francis, John and William, were living there. The family continued to operate the forge until the mid-20th century.

The Medieval Village

The Medieval Village

In the late 12th Century, Saint Mary’s Abbey of Dublin was granted all of Portmarnock, which became a manor or lordship of the abbey. A manor village was later developed, in which tenants made payments in kind by giving ‘plough-days’, ‘cart-days’, fowl for the table, etc. Excavations in 2009 revealed part of the village, which lay south of the line of the present Station Rd. and east of the railway line. The village may also have extended to the north, across Station Rd., where, until the mid-20th Century, Portmarnock House once stood. The village is believed to have been a single planned project, developed under the aegis of St. Mary’s Abbey. It was laid out in regular-shaped plots, up to 65m long, and from 16m to 22m wide. The plots were divided between the ‘croft’ (rear area) and the ‘toft’ (front area). Paths and yard-areas were metalled and each plot had a large well. The dwellings of the village were small, mud-walled, thatch-roofed houses, probably without chimneys. They had packed-clay floors and wooden lockable doors. There was a communal pasture area of 100 acres and also cultivation of crops such as oats, barley, wheat, peas and other legumes, while the nearby tide-mill ground the manor’s corn. Warfare in the Fingal area during the1640s contributed to the decline of the village and by the end of that century it had been abandoned.

Portmarnock House

Portmarnock House, a three-storey-over basement mansion, was built in the 17th Century, off the present Station Rd., in the area of the modern ‘Links’ development. Luke Plunkett was granted lands in Portmarnock in1635, which the family then held, through ten generations, until the mid-20th Century. The grant included ‘the castle’ of Portmarnock, a possible reference to Portmarnock House, or perhaps to an earlier manor-house structure there. This branch of that family, which had its origins in Co, Meath, remained Catholic but ‘loyal’. A chapel in Portmarnock House was used in Penal times. A kinsman, Archbishop Oliver Plunkett, was a visitor to Portmarnock House on a number of occasions. A set of vestments and a prayer-missal used by him were kept in the chapel until the last of the family there, Elizabeth Plunkett, died in 1948. A fire destroyed the house in1953.

The Plunkett Brickworks

The Plunkett family of Portmarnock House had been making bricks from at least the late 18th Century, exploiting the local ample source of brick-clay. In 1880, Thomas Luke Plunkett brought production to an industrial level, establishing Portmarnock Brick and Terracotta Works. Three kilns were operated and manufacturing continued there until shortly after the end of WW I. The main access to the works was by the ‘Old Road’, a lane which ran by the former church and approached Portmarnock House from the west. ‘Portmarnock Brick’ can be seen on a number of local buildings (e.g. the Plunkett Cottages), and in many buildings in Dublin City and County (e.g. Malahide Library, the Red Stables, Raheny, the hospital in Portrane, some city fire-stations, etc.)

Portmarnock Tide-Mill

The Tide-Mill

Tide-mills were used in coastal areas which lacked a river of sufficient volume to drive a millwheel. From the 12th Century, the (Cistercian) Abbey of St Mary, Dublin, held all the lands of Portmarnock and the tide- mill at Burrow, which ground corn, was rented to operators. After the 16th Century Reformation, the Barnewall family of Turvey gained the lands of Burrow, along with the tide-mill. The mill stood at the neck of Baldoyle Estuary, where a bridge (the ‘Mill Bridge’) was eventually built. Behind sluice-gates and confining walls, water from the high tide was trapped, supplemented by the backed-up ‘Sluice’ River. Twice a day, when the tide receded, water was released in a controlled manner, forcing its way through a narrow outlet. This turned a wheel or paddle, which a vertical spindle or shaft connected to the horizontal millstones, located at a higher level. Between the rotating millstones, the corn was ground. In 1799, Thomas Dickinson, of Drumnigh, leased the mill, along with a miller’s house, a garden, and grazing for a cow and a horse. The mill, which fell into disuse in the 19th Century, was damaged by a storm in 1903 and was taken down in the 1940s.

Bridge House

Bridge House was the home of Laurence O’Neill, (1864-1943). He was Lord Mayor of Dublin for seven years, 1917-1924, in probably the most turbulent period in the city’s history. He was last to hold that office under British rule, and also the first to do so after Irish independence. Regarded by many as the greatest Lord Mayor since Daniel O’Connell, he was a constitutional nationalist and a skilled orator. He was briefly (but wrongly), jailed in 1916 and subsequently was close to leaders such as Collins, De Valera, and Cosgrave. As Lord Mayor during the War of Independence, he kept lines open to Dublin Castle and made repeated and significant interventions on behalf of prisoners such as Tomás Ashe. First elected to the City Council in1910, he was elected a T.D. (1922-3), later serving as a Senator (1929-36). Renowned for effective mediation in disputes, his political skills, and his social conscience, he convened the anti-conscription Mansion House Conference in 1918.

Born in King’s Inn St., he inherited his father’s provender business nearby but devoted most of his life to politics. In Portmarnock, he established the Riverside Golf Club, open to all. The nine-hole course on his land ran northwards from Bridge House. In 1934, he donated a site from that land for the original St. Anne’s Church, (‘the Tin Church’). Laurence O’Neill died in 1943 and is buried in the family plot in St. Marnock’s Churchyard, (off strand Rd.)

The Tearmann Cross

On the north side of Station Rd., (near the bridge), there once was a small patch of ground known as ‘The Cross’. A ‘Tearmann’ cross designated monastic boundaries. A local tradition held that this area was used for the burial of still-born and un-baptised babies, suicides, and executed persons.

The Jameson House

St Marnock’s Church

Saint Marnock is believed to have come to Portmarnock in the 6th century and the stone church named after him may have been preceded by at least one wooden church. The stone building dates from the 12th or early 13th century. By then, Portmarnock and its church belonged to the Cistercian monastery of St. Mary’s Abbey, Dublin. Measuring 17.7m by 5.5m, this church had a triple-arched bell-tower, a distinctive feature of early Fingal churches. There was a fenestella, or niche, recessed in the stonework, to accommodate a piscina, (a drained basin in which the sacred vessels were washed). In the 16th Century, the remains of St. Marnock were disinterred and transferred to a specially-constructed chapel in St. Mary’s Abbey. Following the Reformation, the church is believed to have continued in use until about 1615. Following its closure, there was no functioning church, Catholic or Protestant, in Portmarnock for almost 200 years. Burials here of members of both faiths continued, however. The earliest known burial was that of Teresa Plunkett, of Portmarnock House, who, was interred in a family tomb in the chancel of the church in 1672.

St Marnock’s Well

Near St Marnock’s Church was a well dedicated to him, accessed by 16 descending steps. Down the centuries, this was a holy well which was the focus of an annual pilgrimage. Members of the Talbot family of Malahide Castle were particularly faithful to that custom. A ‘pattern’, or Patron’s Day, was held each August, at which customary ‘rounds’ of the well were made. Traditionally, some phenomenal and curative features were associated with the well.

The Ogham Stone

The Ogham stone which stood beside St Marnock’s Well, dated from the period 350 to 600 AD. Ogham Stones were used as grave-markers and also as boundary indicators. In the mid-19th Century, when a cattle drinking-place was installed by the new landowner, the Ogham Stone was broken up and the well closed over. Fr. John Shearman, of Howth, later rescued the stone’s fragments in 1868 and recorded its features and inscriptions. His record is preserved at the Royal Irish Academy, Dublin.

St Marnock’s Church, the surrounding burial-ground, the Ogham Stone, and St Marnock’s Well, are protected monuments.

The Jameson House, (‘St Marnock’s’)

In the 1840s, the distiller, John Jameson acquired nearly 600 acres of land at Burrow, Portmarnock, buying out most of the small-holders there. He built a residence, which overlooked the ruins of the ancient church of St Marnock, after whom he named his house. Keenly interested in golf, he laid out a rudimentary course near the house. Following a fire in 1894, considerable renovation and extension was carried out. An inscription in stone over the original front-door of the house commemorates that work. Nearby was stabling for horses, coach-houses and farm buildings (in the area of the modern office park, ‘The Stables’). An avenue enclosed by iron railings, which survived until the late twentieth century, led from an entrance at South Lodge to the main house. Both gate lodges (‘North’ and ‘South’) have survived, with their distinctive design and (probably) local Plunkett brickwork. The amenities enjoyed by the Jamesons from their country mansion included sailing, shooting and horse-riding. The family’s considerable influence on Portmarnock included the establishment of the first local National School on Jameson land.

The last of the family here, William George Jameson, was best known for his race-horses, his yachting prowess, and his association with high-society and royalty, including the future King Edward V11. After his death in1939, the house was sold and it has since been used as a hotel.

Walter Frederick Osborne

Walter Osborne (1859-1903), had much association with Portmarnock and the local Jameson family. His paintings, in oil, water-colour, pastel and pencil, embracing portraiture, landscape, and other subjects, continue to be acclaimed. A number of his works feature scenes of sea, sands, grassy dunes in the Burrow area, along with John Jameson’s dairy cows. For some years, Osborne spent the whole summer here, staying in the house of the Reilly family, across the road from the Jameson mansion. The Reilly children appeared in some of his works, notably in ‘The House Builders’ (1902,) in which twins, Martha and Theresa feature, and ‘The Lustre Jug’ (1901). Osborne’s ‘Milking Time at St. Marnock’s Byre’ (1890s) depicts a milking-time scene in the Jameson cow-byre. This was located in the area of the modern ‘The Stables’ business park, south of the former Jameson residence.

Martello Tower & Aviation History

Carrickhill Martello Tower

Carrickhill Martello Tower is one of twenty-six towers along the Dublin coast, twelve of which are in Fingal. The name ‘Martello’ derived from Cape Mortella, in Corsica, where a tower of such design had withstood heavy attack. Built as a defence against possible invasion in the Napoleonic period, most of these towers were completed between 1804 and 1806.

On the gun-platform on top there was a twenty-four pound, rotatable, cannon. A small type of furnace was used for heating metal shot. A fusillade of hot shot could devastate the sails of a war-ship, shattering its masts and spars, and probably setting the ship on fire. However, this Martello Tower, like all the other twenty-five, never fired a shot in anger!

On the first floor, the Carrickhill tower accommodated twelve to fifteen soldiers. These were drawn from companies that, having been trained at the Royal Artillery Academy in Woolwich, London, were then stationed at Islandbridge. The men wore colourful uniforms which were often quite individualistic. Their equipment, including sword, musket and ammunition, weighed about seventeen kilograms.

The ground floor held the ammunition magazine and a store. From the roof, nearby towers at Howth, Ireland’s Eye, Robswall and Portrane, could be seen. There was once a small pier or quay beside the tower. This may have been used to bring in construction materials when the tower was being built, but the pier was in ruins by 1835. The tower was disarmed in 1874, and was later sold and adapted for private residential use. A roof was added to the gun-platform, along with castellations and windows.

Not far from the Martello Tower was the well of Tobermaclaney or ‘Tobar Mic Láine’. This was described, in1830, as ‘a small well of clear water, lying forty-six yards (42m) south-west of Carrickhill Martello Tower’.

Aviation History Made at Portmarnock

Between 1930 and 1933, Portmarnock Beach, the ‘Velvet Strand’, was the take-off point for history-making trans-Atlantic east-west flights. Nowadays, the sculpture, “Eccentric Orbit’ at the sea-front commemorates those brave aviators.

The ‘Southern Cross’

In 1930, the world-famous Australian flyer, Charles Kingsford-Smith came to Dublin with his aircraft, the ‘Southern Cross’, a Fokker three-engined monoplane. His navigator was Captain J.P. (‘Paddy’) Saul (1895-1968), a Dubliner with an early Malahide connection. Before turning to flying, Saul had travelled the world under sail. Co-pilot was Dutchman, Eric Van Dycke, while the wireless operator was the New Zealander, John Stannage. Watched by up to ten-thousand people, the ‘Southern Cross’ left Portmarnock Beach at dawn on June 24th, 1930. It landed at Harbour Grace, Newfoundland, over thirty-one hours later, thus completing the second-ever non-stop, east-west, flight between Europe and North America.

The ‘Heart’s Content’

In 1932, a young but experienced flyer, the Scot, Jim Mollinson, brought his aircraft, ‘Heart’s Content’, to Portmarnock, intent on his own piece of history. Previously an associate of Charles Kingsford-Smith in Australia, Mollinson now had the the benefit of charts prepared by Captain Paddy Saul, (who had been the navigator on the ‘Southern Cross’ flight from here, two years earlier).

The ‘Heart’s Content”, a single-engined Puss-Moth monoplane, took off from Portmarnock at 11am on August 18th, 1932. He was seen off by his new wife, the world-famous aviator, Amy Johnston, the Lord Mayor Alfie Byrne, and thousands of well-wishers. Flying without a radio, to save fuel, Mollinson landed at Pennfield Ridge, New Brunswick, thirty hours later, becoming, at the age of twenty-five, the first person ever to fly the North Atlantic solo, non-stop, east-west.

‘Faith in Australia’

In July, 1933, a third east-west trans-Atlantic flight was being prepared for take-off from Portmarnock. The pilot was the Australian, Charles Ulm, another former associate of Kingsford-Smith. His aircraft was the ‘Faith in Australia’, a three-engined monoplane. In an unfortunate but vital mishap, a wheel of the plane slipped off the wooden ramp and sank in the sand. Attempts to re-position this led to further mishap and, with the incoming tide approaching, the venture had eventually to be abandoned. Captain Paddy Saul was also present on this occasion.

Robswall Martello Tower

Perhaps 6,000 years ago, the first residents of this region, Neolithic or early-Bronze-Age people, came to the area which is now Robswall Regional Park. They made arrowheads, blades, axe heads, hammer-stones and the like, and they regularly ate oyster and duck. Two features of the area, Patrick’s Well, and Paddy’s Hill, were, by tradition, named following a visit by Saint Patrick. For over three centuries, the monks of St Mary’s Abbey held the all of Portmarnock, including the lands of Robswall. After the monasteries were suppressed in the 16th Century, Robswall was acquired by the Barnewall family, and then, in 1890, by the Malahide Estate.

Robswall Coastguard Station

First set up Treasury Order in 1822 and based on branches of Revenue, the Coastguard’s main role was to prevent smuggling and help detect illicit distilling. From 1856, now under Admiralty control, the emphasis was on shipping safety, assisting vessels in distress, and signaling storm-warnings to mariners. In 1886, the new station at Robswall was opened, replacing one in Malahide. It had living accommodation for a Chief Officer, six men, and their families, a boathouse with a slipway, a watch office, flagpole, and workshops. In May, 1921, during the War of Independence, Robswall, like four other Fingal stations that night, was attacked and burnt down. Remaining sections of the Coastguard Station’s boundary wall can be seen on either side of the roadway near High Rock. (Elsewhere in Portmarnock, Coastguard officers lived in two cottages near Portmarnock Point.)

Robswall Martello Tower

Now known as ‘Hick’s Tower’, this was one of two built in the adjoining Portmarnock townlands of Robswall and Carrickhill. Like the Carrickhill Tower, to its east, (and ten others on the Fingal coast), it was completed between 1804 and 1806 to counter the threat of invasion in the Napoleonic period and guard Malahide harbour. Manned by the Royal Artillery, it held thirty barrels of gunpowder, a cannon, a supply of cannon-balls, and 1,700 litres of water. It also had a pigsty, privy, flagstaff, and a shot-furnace. The invasion never came and the cannon on the roof remained unused. By1874, the tower was decommissioned and in 1897 it was let to Lord Talbot. In 1909, Frederick G. Hicks, an architect, acquired the building for £175, converting it to residential use and adding a roof-top conical, two-level, attic space, and also a bronze weather-vane, depicting a galleon under sail.

Robswall Castle

The Castle site is believed to have been occupied from the 13th Century by monks of Saint Mary’s Abbey, to whom fishermen entering Malahide Harbour paid a toll of fish. Essentially a Norman tower-house, it was a three-story, square building, designed to command the passage to Malahide harbour. In pre-cannon times, it was considered strongly-fortified, with a number of wide-angle, slit, windows, used for a look-out, archery and possibly musket-fire. A circular stone stair led to the first floor. There, a small ‘garderrobe’, or privy, overhung the castle wall. Eight stone steps led to the battlements, where there was a watch-tower. After the suppression of the monasteries in the 16th Century, Patrick Barnewall of Turvey held the Castle, from which time has come ‘Rapunzel’-like legend. This concerned the beautiful daughter of an aging Barnewall, enclosed in the Castle by him to keep her from her heart’s desire. That was a young Talbot man, of Malahide Castle, who, nevertheless, managed to scale the walls and gain the heiress! In 1890, the Malahide Estate took over the Robswall lands, then using the Castle as a residence for the land-steward. Modernisation in the 20th Century resulted in the loss of the third-floor section of the Castle, which continues now as a private residence.

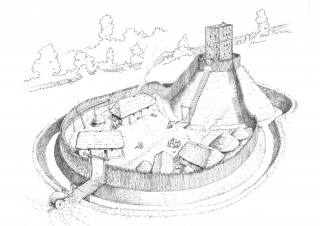

The Motte & Bailey monument

In the late 12th century, a motte- and bailey settlement was established at Wheatfield, one of several hundred such erected by the Normans, country-wide. Until the late 12th century, the last Danish King of Dublin, Hamund Mac Turcaill, had held the lands of Portmarnock and surrounding areas but he was then overcome by the newly-arrived Anglo-Normans. The Talbot family constructed a motte and bailey base at Wheatfield. Over time, they built Malahide Castle and moved there. Motte and bailey fortified structures were round earthwork mounds, tapering upwards and surrounded by palisade fencing. There was usually a wooden tower on top and an adjoining stockade where animals could be enclosed. This had barns, stables and sheds which housed workshops. The earthen mound of the motte and bailey at Wheatfield, in St Helen’s townland, has survived as a protected monument.

Resources

Portmarnock, Its People and Townlands. A History

Garry Ahern

2013The Velvet Strand

A History Of Portmarnock

Tadhg Kennedy

1984Portmarnock and the Plunketts

1850 – 1918

The Portmarnock Brick and Terracotta WorksPortmarnock Uncovered

C McMahon & B Ennis

2014Portmarnock, A Closer Look

The Portmarnock Youth Project Team

1985Shooting Suns and Things transatlantic fliers at Portmarnock Kingsford Press

1986Portmarnock Peninsula-the Natural History

D.C.C Planning Dept

1985Baldoyle, Portmarnock & Sutton A Local History,

M. J. Hurley

2009Messines to Carrrick Hill,

Thomas Burke,

2017The Medieval Vill of Portmarnock in Medieval Dublin,

Colm Moriarty,

The Motte, Wheatfield, Portmarnock, Joseph Byrne in Fingal Studies,

2011Around and About Malahide

Roger Greene

2012Short Histories of Dublin Parishes

Part XV

Carraig ChapbooksInventory of Outstanding Landscapes An Foras Forbartha, commissioned by The International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources

Malahide Past and Present

Noel Flanagan

1984Lewis’ Dublin

C. Ryan

2001Ten Dozen Waters

The Rivers and Streams of Co. Dublin

Joseph W DoyleNorth Dublin City And County

Dillon CosgraveVernacular Architecture of Fingal

Brendan Lynch

2007By Swerve of Shore,

Fewer

1998The Martello Towers of Dublin, Bolton/Carey/Goodbody/Clabby,

2012The Villages of Dublin

J Wren

1987Laurence O’Neill (1864-1943) , Patriot and Man of Peace,

T.J. Morrissey, S.J., D.C.C.

2014